Hadija Steen Mills is a Maternal & Child Health MPH student at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. Their work centers around creating more equitable ways of educating people about public health and the resources available to them. During the pandemic, Hadija worked to set up a community-focused COVID-19 testing site. Read their responses to the questions below to learn more about their experience at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Where did you attend undergraduate school and what did you study? [Hadija] I attended the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. I completed a self-designed degree in Human Sexuality with a focus on Reproductive Justice and disparities. A self-designed degree is a cool way to go into a niche area like that, not a lot of people know about it. There are processes and proposals in the design of the degree, but there is support embedded into the process to guide students.

What drew you to public health? [Hadija] My interest has always been in the area of disparities. Human sexuality is a connection point, it is a gateway for everyone. Sexuality is a topic full of values so being able to educate and connect with folks in a trauma-informed and non-judgemental way has always been of interest. Approaching such a complex subject with caring can open the door further to talk about inequities, injustices, and paths to liberation.

What area of public health do you care the most about and why?

[Hadija] In my work before applying to graduate school, I was part of a national study funded by the Office of Population Affairs that was a rigorous evaluation of sexual health curricula. To receive certain types of government funding, you have to use tools and curricula approved by the Department of Health and Human Services, and I got to help evaluate one of those tools that will be used nationally by educators. In being part of that process, I got to help do an LGBTQ overhaul, reviewing the curricula for inclusivity and heteronormative and cisnormative bias. After being immersed in that type of research, I was encouraged to apply to graduate school so I could continue to lead and guide that work.

How are you working to advance health equity? [Hadija] Lately, I’ve been working on COVID-19 disparity mitigation strategies. I’ve been working really hard to implement some of the various strategies that I’ve designed. My work is related to healthcare reparations, which is a larger approach. This means creating a trauma-informed and culturally humble implementation strategy that can attempt to create trust with communities who are being impacted by negative health outcome ‘X’ which right now is COVID-19.

Secondly, I’m working to create change in the bureaucratic systems that create barriers and perpetuate these disparities. These strategies build a feedback loop through uplifting the issue, re-investing in communities, and dismantling barriers. The goal is always to not further hurt communities that are already hurting. I’m finally getting some tangible research numbers that can create real policy change.

Can you tell me about the COVID-19 Community Testing Site you designed?

[Hadija] Before George Floyd was murdered, I had been exploring COVID-19 disparities. After his murder, the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) recommended that the people who attended the George Floyd protests get tested for COVID-19. The problem was that their testing sites weren’t accessible to everyone. I had experienced this myself and had been hearing similar feedback from community members. So, I decided to connect with the folks at MDH to elevate that these sites weren’t accessible. I also began working to design and create my own community-focused testing site. I layered trauma-informed, harm-reduction, and culturally-humbled practices into designing a testing site that could better serve under resourced communities. A lot of these communities are disproportionately affected by various disparities, but currently COVID-19 is in the limelight, so creating a service that doesn’t harm folks more than they’re already hurting was really important.

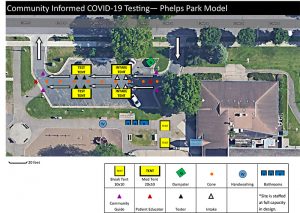

I found out later, barriers to funding caused a lot of setbacks in timely responses. Yet another systemic barrier perpetuating disparities. After countless meetings, I was eventually advised to contact the Minneapolis Health Department. I explained the situation and the needs of these communities with them about why to erect the testing site that I had designed. They finally said yes! For the first testing event, we partnered with NACC (Native American Community Clinic) to build a testing location at Phelps Park. In addition to the Phelps Park temporary testing site, we were also able to do some pop-up testing events around the Twin Cities. We have helped test over 4,000 people.

In all of this, I’ve fought to make sure that all of our community workers have been paid very well. As individuals who represent socially, politically, and economically marginalized communities, paying them well is an important aspect of disparity work. That was one of the conditions of partnering with the Minneapolis Health Department that thankfully they supported.

Why did you choose to come to the UMN School of Public Health? [Hadija] I loved my undergrad experience at the University of Minnesota and the School of Public Health is very well known and well respected. There are faculty that I’m very interested in working with over the next two years. I have been getting to work with Assistant Professor Kumi Smith and am interested in the work Associate Professor Rachel Hardeman and my faculty advisor Jaime Slaughter-Acey focus on.

In what ways is the school a good fit for you? [Hadija] It’s been remarkable how supportive the School of Public Health has been in supporting my COVID-19 disparity work. I’ve even been invited to do several speaking engagements at the University. It really is an honor and I’m curious to see what the rest of the year brings! I have no idea if I’d had a typical grad school experience thus far. It’s been really interesting to feel like I have some peers among the faculty. They’re in my corner which has been an honor.