Every day, Americans clean their homes and businesses with household cleaning products that most assume are safe. But is that actually the case? The truth is a majority of chemicals in these products are thought to be safe from being toxic. However, the exposure amount or time that is safe for using those products before possibly suffering bad health effects was probably never tested, likely because researchers and regulators have lacked a reliable method to do so.

“When you think about how we use products — how much, how long or how frequently we use them — all of those factors can add up to how much of a chemical we are exposed to,” says School of Public Health Assistant Professor Susan Arnold. “But, measuring exposure is complicated, expensive and you can’t just put a sensor on someone who’s using the product and get an accurate number.”

To help protect consumers, Arnold has developed and evaluated a method to predict the amount of chemical evaporating from liquid household cleaners and estimate the amount people would be exposed to over time. The results were published in the Journal of Exposure Science & Epidemiological Research.

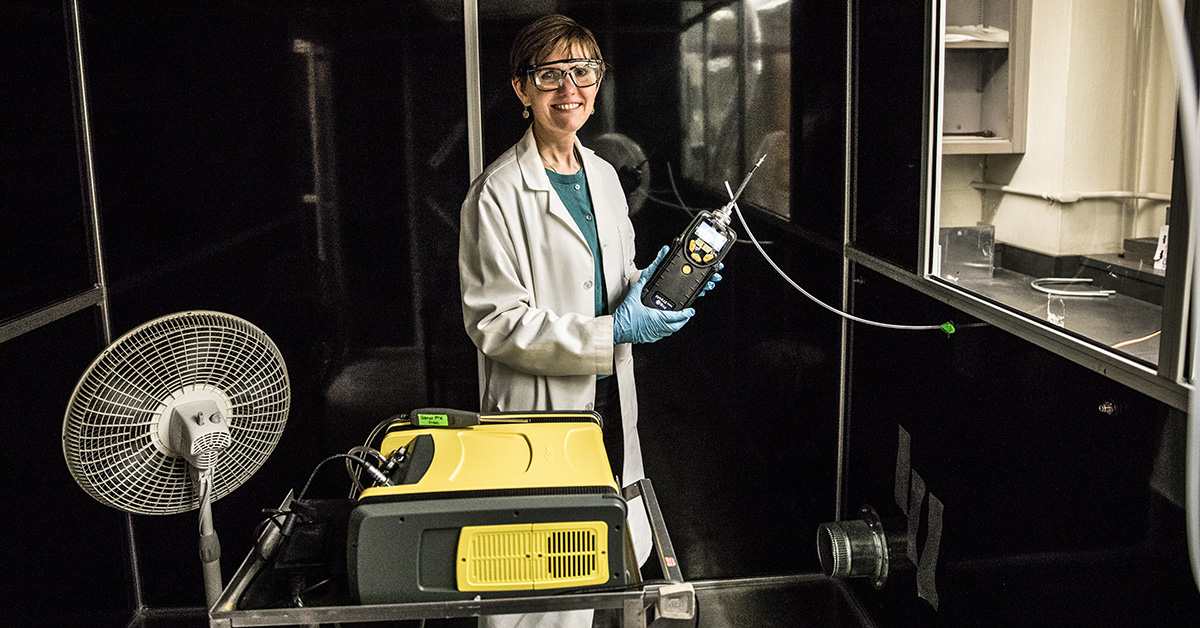

For the study, Arnold began by realistically simulating the mopping of a floor in a special laboratory chamber where airflow and other factors could be strictly controlled. Inside, she measured chemical levels in the air using a new, commercially available portable device that can simultaneously measure the levels of multiple chemicals. Specifically, Arnold zeroed-in on measuring how much of the floor cleaner’s acetic acid would evaporate off the floor into the air over the course of mopping. She then used the acid’s rate of evaporation, called a “generation rate,” in a mathematical model that can estimate the amount of chemical people could be exposed to when mopping in a real-world setting, such as a kitchen.

Arnold later repeated the test inside a real house and compared the actual chemical levels present during mopping to the amounts predicted by her exposure model. She found that the measurements were very similar, indicating that her method for estimating chemical generation rates works and the model is accurate.

“This means the model and generation rate could be beneficial for risk assessors and product companies because it can reveal formulations containing chemicals that can trigger or aggravate health problems, such as asthma,” says Arnold. “In response, they might consider reducing the levels of the potentially irritating chemicals or provide warnings or instructions on the packaging describing how to use the product in a way that’s safest.”

Arnold is currently pursuing related research looking at chemical exposures from products using spray nozzles.