The School of Public Health, Medical School, and Masonic Cancer Center provide initial funding for a bold initiative

It’s extraordinarily difficult to transfer cancer research findings from one country to others across the globe. Each country has different populations, cultures and environments, research approaches, and regulatory systems. And, when it comes to one of the worst cancer-causing agents, they often have drastically different types of tobacco products.

For example, snus, a finely cut oral tobacco product used in Sweden, appears to have minimal harmful health effects when compared to other oral tobacco products. This is most likely due to its relatively low levels of cancer-causing chemicals. But what are the opportunities for reducing the cancer risk of drastically different oral tobacco products popular in India, a country with more than one third of the world’s oral cancer cases? It would take systematic research and robust, coordinated prevention practices and policies to make that happen, but such actions could save millions of lives.

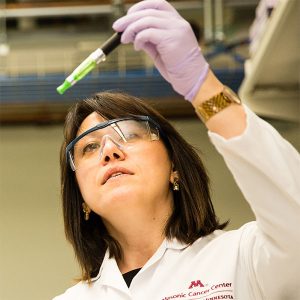

To make global research more effective and methodologically consistent and to move the dial on world-wide cancer deaths, Irina Stepanov, Mayo Professor in the School of Public Health, has launched an initiative called the Institute for Global Cancer Prevention Research. What’s more she has secured initial funding to support her vision from the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Medical School, and Masonic Cancer Center.

Stepanov is internationally recognized as a top researcher in tobacco carcinogenesis — the science of causes and mechanisms of cancer. Her focus is on the chemistry of tobacco products, exposures in users, and how and why tobacco use leads to cancer. She was the first to discover that while e-cigarettes contain virtually no N-nitrosonornicotine — a chemical that can cause oral cavity and esophageal cancer — it can form in an e-cigarette user’s body when they take in nicotine through the device. This discovery changed attitudes toward what was initially considered a product that should not have cancer risks.

What fuels all of Stepanov’s work is the suffering cancer causes.

“Worldwide, we are making significant progress in treating cancer,” says Stepanov. “But even if there is treatment, going through chemotherapy or radiation therapy and having, maybe, a few percentage points of survival is terrible. We have to make more progress in preventing cancer in the first place.”

In her lab at the Cancer and Cardiovascular Research Building, Stepanov centers her work on three areas, all aimed at preventing cancer: 1) understanding the role of how carcinogens metabolize and damage DNA to gauge a person’s cancer risk, 2) developing novel biomarkers that signal exposure to environmental toxicants and carcinogens, and 3) monitoring toxicant and carcinogen levels in traditional and emerging tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes or heated tobacco products.

A global focus

Stepanov has been doing global cancer-prevention work for over a decade. To increase research capacity in places where it is desperately needed, she and UMN colleagues Dr. Samir Khariwala and Professor Dorothy Hatsukami worked on several projects developing laboratory and clinical tobacco research capacity in India and China. She is also working towards developing a collaborative research program in Malaysia. But it’s not only capacity that’s important, but also a globally consistent way of doing research, which the World Health Organization has identified as a key gap in informing global tobacco control.

Stepanov has been doing global cancer-prevention work for over a decade. To increase research capacity in places where it is desperately needed, she and UMN colleagues Dr. Samir Khariwala and Professor Dorothy Hatsukami worked on several projects developing laboratory and clinical tobacco research capacity in India and China. She is also working towards developing a collaborative research program in Malaysia. But it’s not only capacity that’s important, but also a globally consistent way of doing research, which the World Health Organization has identified as a key gap in informing global tobacco control.

“Dr. Stepanov has devoted her life to stopping the ravages of cancer by keeping it from developing in the first place,” says John Finnegan, dean of the School of Public Health. “It’s an incredibly tall order, but she has the skills, experience, and drive to move the world closer to that goal. My colleagues and I chose to fund her new institute because we have faith in her ability to make significant, lasting, and positive changes in how we do research across the globe and to build effective partnerships.”

The Institute for Global Cancer Prevention Research will focus on growing partnerships and research capacity, and the translation of research findings into prevention practices and policies. Following Stepanov’s commitment to conducting such work in populations that bear the disproportionate burden of cancer, the institute will target its efforts towards low- and middle-income countries, as well as immigrant communities locally.

“The research our institute is focusing on is not just research for its own sake, but it will ideally directly inform on-the-ground practices and policies that will serve to prevent cancer,” says Stepanov.

Stepanov recognizes that the institute can’t achieve all she wants it to do right away. “You need to start in a focused way and then grow, and it’s best to start from the existing point of strength, with something that you already know and are already doing,” she says. Help of a steering committee consisting of dedicated UMN colleagues was critical in defining the institute’s mission and initiating its work. The committee includes Hatsukami, who is a fellow tobacco control researcher and the associate director for Cancer Prevention and Control in the Masonic Cancer Center, and the Medical School’s Dr. Rahel Ghebre, a gynecologic oncologist with extensive experience in global research and training. Hatsukami serves as the institute’s deputy director. The steering committee also includes Seanne Falconer, executive & associate director for administration with the Masonic Cancer Center, who provides key insights into the strategic partnerships and development, and Tonya Gannelli, global operations manager, who brings expertise in managing complex multi-site studies as part of large NIH-funded programs.

Vision into action

The institute has three initial focus areas: 1) tobacco control, 2) environmental causes of cancer, and 3) infectious agents and cancer.

For the first, tobacco control, the vision is to establish a global consortium for tobacco product evaluation, involving partners and research sites in countries across the world. Currently, Hatsukami and Stepanov are collaborating on a proposal for a seven-site global study of the impact of electronic cigarettes on human health, in response to a major National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research UK Grand Challenge program. The proposal will serve as a blueprint of the consortium that the institute aims to develop.

Being part of the Division of Environmental Health Sciences, Stepanov’s research interests expand beyond tobacco as a cancer-causing agent. Building on her long-term relationship with India, Stepanov wants to develop a research hub in Mumbai for studies on environmental causes of cancer. Her collaborative efforts with Khariwala, who is a professor and the vice-chair in the Medical School’s Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, led to establishing connections with the Center for Cancer Epidemiology in Mumbai, which has gene sequencing capacity and research cohorts with thousands of participants with different types of cancer from whom they collect data and biological samples. Stepanov wants to leverage this connection to study the role of air pollution in the risk for lung cancer and head and neck cancer in nonsmokers. Such research is uniquely possible in India, where a significant proportion of the population uses smokeless tobacco, but there are very few smokers.

Working with Indian partners will help researchers at the School of Public Health, and across the University and the world to ascertain risks not only for lung or head and neck cancers, but also other types of cancers, for example stomach cancer and cervical cancer.

“We’ll be able to ask questions that we can’t ask here in the U.S.,” says Stepanov. “We can better understand the mechanisms and the risks for cancer in certain populations and then see how that knowledge can be applied for cancer prevention in other countries, including here in the U.S. And of course, we will be addressing key local priorities in cancer prevention and continue to build relevant research capacity in India.”

To address infectious agents and cancer, the institute aims to develop a fellowship program for early career investigators globally. Initially, the institute plans to support a small cohort of fellows from low- and middle-income countries in Africa, to focus on developing skills such as conducting research, understanding methodologies for research projects, and how to apply for grants and write papers. The expectation is that these fellows will become committed, successful researchers and partners in the field of cancer prevention.

People have big ideas all the time, but they don’t often do the hard work or have the opportunity to turn them into reality. Stepanov is doing that hard work and is fortunate to have the resources and support of her colleagues to pursue her ambitious vision.

“Some cancers are nearly 100% preventable,” she says. “Knowing that people suffer and die from cancers that could have been prevented literally breaks my heart and keeps me up some nights. We at the University of Minnesota have world-class researchers with the skills and expertise to do something about it, so building this institute as a platform for global outreach is what we should be doing, right? And creating opportunities for research and career development around the world, particularly in places with limited resources, makes this effort even more meaningful and rewarding.”

The School of Public Health named Irina Stepanov a Mayo Professor in 2020. The professorship is the oldest at the school and funded with a bequest from the estates of Drs. William and Charles Mayo, who also provided initial financial support for the school itself. The goal of the honor is to recognize distinguished researchers. For three years, Mayo Professors receive $50,000 each year to expand their work, hire research assistants, improve their labs, etc. They carry the title during their time at the school and in retirement as Mayo Professor Emeritus.