The COVID-19 pandemic is making education difficult or impossible for all types of learners. One group in particular are people incarcerated in Minnesota’s prisons who can’t take on-site classes because of quarantine restrictions. School of Public Health Associate Professor Ruby Nguyen responded to a call to college instructors from the state prison system for distance learning courses and created an introductory public health class that will teach incarcerated residents how to understand the issues of today, and possibly, open the door to a future career in the field.

“It is a critical time to engage people in prison who wouldn’t otherwise know about epidemiology, and it’s particularly rewarding to do so with people whose lives are directly affected by public health and its interventions,” says Nguyen. “I’m excited to teach this class because it is a challenge that is hard, interesting, and helpful.”

A change of plans

When the pandemic struck, Minnesota’s prisons closed to outside visitors to protect the health of inmates, which forced the facilities to postpone plans to offer in-person “open university” classes. Still wanting to offer inmates learning opportunities, the Minnesota Department of Corrections (DOC) established a partnership with Metro State University in Saint Paul to develop distance learning courses.

“In-person education is our goal for the prison’s open university concept, but with COVID-19 that’s just not possible right now, so, we needed to find new ways to go about it,” says Janet Morales, an education specialist with the DOC.

To create alternatives, DOC and Metro State University sent an email to faculty across the country seeking ideas for courses, including from the University of Minnesota. The other instructors are from Harvard and Morehouse University.

Nguyen responded with her idea for an undergraduate-level public health course.

The new fall class is a one-credit, 15-hour course called Epidemiology in Society and covers how diseases are spread within populations of people and our communities. The course is funded by a grant from the DOC.

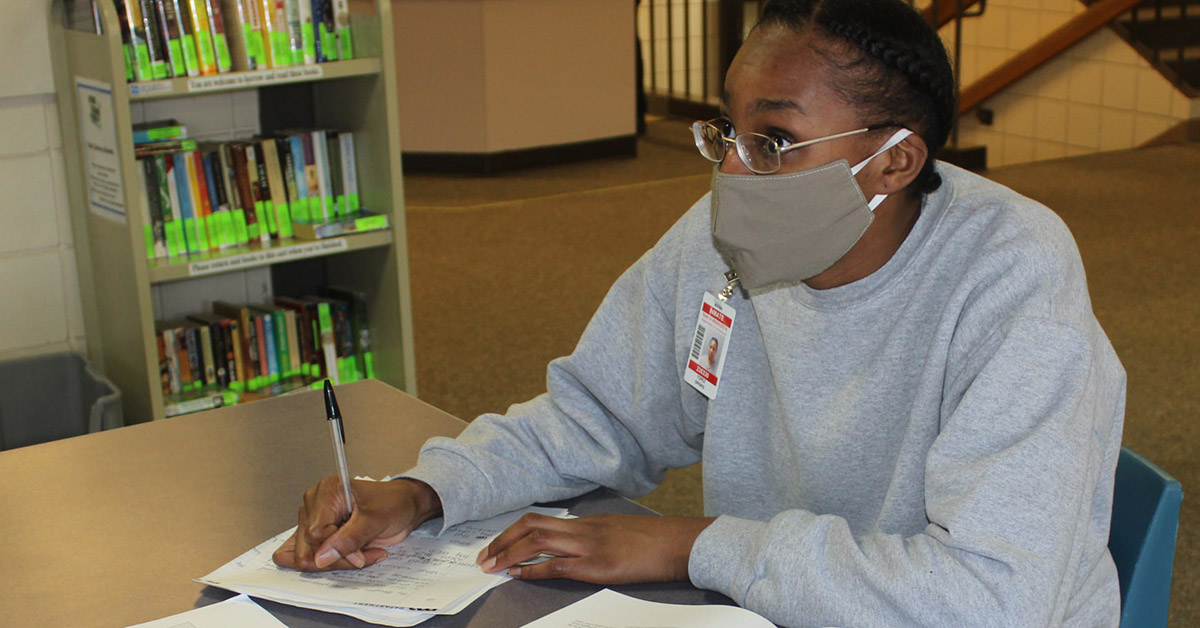

The course will teach prisoners how to use epidemiologic information, understand the role epidemiology plays in their lives and society, and to be an advocate for epidemiology by demanding that health policies and practices be based in facts and knowledge. Lectures for the class will be played on prison television systems for students to watch and will be paired with textbook readings. Students will be required to complete weekly assignments and a final exam.

A future course

“The class is meant to be a general overview of what epidemiology is and also an introduction to the field as a potential career opportunity,” says Nguyen.

“This class will be the best — and hardest — course that we offer right now,” says Daniel Karpowitz, assistant commissioner for policy, research and planning with the DOC.

Karpowitz is an experienced prison education visionary who is working with the Gov. Walz Administration to enhance and expand the state’s programs.

“The course and our open university program are an attempt to tap the capacity of potential students who are incarcerated and pair them with great institutions, such as the University of Minnesota, to prepare them for their future careers,” says Karpowitz. “I think public health may be a field where formerly incarcerated people are not only welcome, but their life and prison experience may be an asset.”

No computer? No problem

Nguyen says that class will not only challenge the students, but also herself as a teacher.

The DOC’s open university program is new, which means they do not yet have the infrastructure and educational resources typically available to students.

“They don’t have access to the internet, computers to type on — or even me,” says Nguyen.

To make the course work, Nguyen found a low-cost textbook that the prison students can use, has assembled a course packet to be printed and bundled, and is recording the lectures at home that are passed on to the DOC.

“The students will complete assignments using pen and paper, which will then be sent back to me,” says Nguyen. “It works a lot like correspondence courses from back in the day.”

It’s an old school, creative approach to address a very complex, modern problem. In the process, the class will educate a very isolated group of people who are deeply affected by current issues in public health. What’s more, the course may eventually pave their way to helping solve them.