Illnesses like heart disease, HIV, and Ebola kill millions of people every year. Prevention is the first defense against them, but once contracted, reducing their impact largely rests on the development of vaccines and medications that must be proven safe and effective before general use. For more than 40 years, the School of Public Health’s Coordinating Centers for Biometric Research (CCBR) has attracted multi-million dollar grants to test vaccines, drugs, and medical treatments that transform health care and help protect people from the worst diseases around the world.

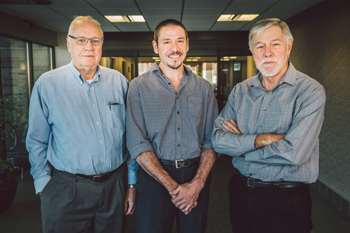

“We’re drawn to addressing the most pressing public health problems,” says CCBR principal investigator and biostatistics professor Jim Neaton.

According to Professor John Connett, also a principal investigator, the center’s international reputation and success stem from how well it handles the data from studies and the people who participate in them.

CCBR stresses to its staff and collaborators the importance of closely monitoring data as it’s being collected and providing feedback to the personnel running research sites on how well the process is working.

Just as importantly, the center puts great emphasis on establishing good relationships with study participants.

“Friendly, personal contact is really, really important in clinical trials and it’s essential for good follow-up rates,” says Connett. “It shows people that their participation really matters for scientific value — even if they don’t benefit directly from the treatments or interventions.”

With Neaton’s and Connett’s leadership, CCBR has become one of the most trusted and exacting national and international centers for the coordination of multi-center clinical trials.

“It starts with the science,” says Jason Baker, MD, a researcher with the Department of Medicine and Hennepin County Medical Center who has worked with CCBR on his own cardiovascular and HIV studies. ”They really know how to employ their experience designing, implementing, and conducting trials and studies. The data they gather is complete and they use the best methods for analysis.”

Professor Cavan Reilly, who was appointed as CCBR’s associate director last year, says that, at its heart, the way the center functions and conducts trials is unique and leads to better studies.

In most clinical trials, the managers and protocol coordinators are often nurses, with a doctor managing the staff. But at CCBR, the people who do the day-to-day work on clinical trials are trained biostatisticians who work as equals with their clinical colleagues.

“Biostatisticians place a great emphasis on acquiring high-quality data by tracking it, looking for missing pieces, and formatting it for easier analysis,” says Reilly. “Also, breaking that hierarchical relationship between the staff and a boss creates an opportunity to do the work [free of any bias] and according to rigorous biostatistical standards.”

Finding the benefits of quitting smoking

The first major trial CCBR coordinated came in 1972 with the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) that demonstrated how the center’s methods produce high-caliber, influential studies. MRFIT looked at more than 12,000 middle-aged men to determine if quitting smoking, lowering blood pressure, and reducing cholesterol through diet could reduce heart disease. Scientists have long-considered the quality and completeness of the data from the study to be exceptional, and have used it in more than 300 papers — most recently in a 2015 paper in the Journal of the American Heart Association showing the positive effect of the interventions used in MRFIT to reduce the risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events

Following MRFIT, CCBR conducted other major cardiovascular health research in the 1980s that studied the effects on lung health of quitting smoking and taking certain medications, and the long-term survival rates of people who stopped using cigarettes.

At the the height of smoking in the United States, the results from this research showed for the first time that quitting smoking is good for your health and can improve lung function. The study signaled a huge victory for public health and the superior quality of the data meant that the results couldn’t be refuted by tobacco companies and smoking supporters.

Changing how we treat HIV

In the next decade, CCBR turned its attention to the confounding, emerging threat of HIV/AIDS, which went from five cases in Los Angeles in 1981 to 100,000 people in the U.S. with the disease by 1989.

“It was a mysterious illness and we wanted to make a major contribution to this critical infectious disease,” says Neaton.

In 1990, CCBR received a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease to serve as the study coordinator for the newly formed Community Programs for Clinical Research AIDS (CPCRA). Over the next several years, Neaton and his colleagues worked with more than 100 sites across the United States to design and conduct trials aimed at slowing the progression of HIV as well as preventing and treating opportunistic infections that often accompany the disease.

As a result of this work, Neaton, along with U.S. and international colleagues, were awarded a grant to conduct interventional HIV trials. This new group was called INSIGHT (International Network for Strategic Initiatives in Global HIV Trials), and studied HIV and influenza in 40 countries.

CCBR coordinated two of INSIGHT’s trials — SMART and START — and each had a major impact on HIV treatment. SMART established that episodic use of antiretroviral HIV treatments did not protect patients from the side-effects of the drugs and led to increases of both AIDS and non-AIDS conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer.

START showed the health of HIV patients can be greatly bolstered if they begin taking antiretroviral drugs before their immune system begins to suffer, rather than following the more common protocol of waiting for a high viral load to start treatment. This signaled a global shift in how HIV is managed.

Responding to Ebola

Beginning in 2014, CCBR put its experience, operating philosophy, and methods to full use to respond to the Ebola crisis.

One of the most severely stricken countries, Liberia, asked the U.S government for assistance in dealing with the epidemic. Representatives from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in turn contacted Neaton and asked him to respond. Neaton flew to Monrovia in October of 2014 at the height of the outbreak and visited 10 potential trial sites.

“In West Africa at the time, the health care infrastructure was zilch, and it was in complete disarray,” says Neaton. “The health care facilities were abandoned because the doctors and nurses had all died of Ebola.”

By February, Neaton and his colleagues had initiated a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled vaccine trial at the refurbished Redemption Hospital in Monrovia, with a pharmacy and data management center on the U.S. embassy grounds.

Soon afterward, the epidemic suddenly waned. It was good news for the people of Liberia, but the epidemic ended too soon to complete the trial, which was only able to verify the safety and clinical effectiveness of two vaccines, not their ability to actually prevent Ebola.

But Neaton and his fellow CCBR investigators know that, even though the immediate threat of Ebola is gone for now, many questions remain about preventing an Ebola outbreak and treating the disease.

“Our work in Liberia continues with a large study of Ebola survivors, a trial of a novel antiviral drug for men with Ebola virus in their semen, and another large vaccine trial that will be conducted in Guinea, Sierra Leone, Mali, and Liberia to establish the safety and immunogenicity of three vaccine strategies,” says Neaton. “We’re conducting these trials so that we’re better prepared for the next epidemic.”