Around the world, large numbers of HIV-positive patients who initially start treatment are dropping out of a health provider’s care. Patients may stop seeing their provider for various reasons, including poor understanding of their disease and its treatment, lack of social support, and difficulty communicating with their HIV clinic. Patients who drop out of care risk developing severe illness or even death, and are at a greater risk of spreading HIV to others.

The situation is certainly true for Ethiopia, where a study found that over a quarter of patients are no longer in care one year after starting HIV treatment. Now, a new program developed by University of Minnesota School of Public Health Professor Alan Lifson and his Ethiopian partners aims to reverse the trend by pairing Ethiopian patients with a fellow HIV-positive peer support worker to support them in managing their illness.

A study of the program was published in the Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, and builds on previous work in Ethiopia by Lifson.

The study tested the efficacy of partnering community support workers with 142 HIV patients in rural Ethiopia. The researchers found that 94 percent of patients with support workers were still in care after 12 months. According to Lifson, the relationships also produced significant improvements in the patient group’s health care knowledge, self-perceived physical and mental quality of life, acceptance of HIV status, and feelings of social support.

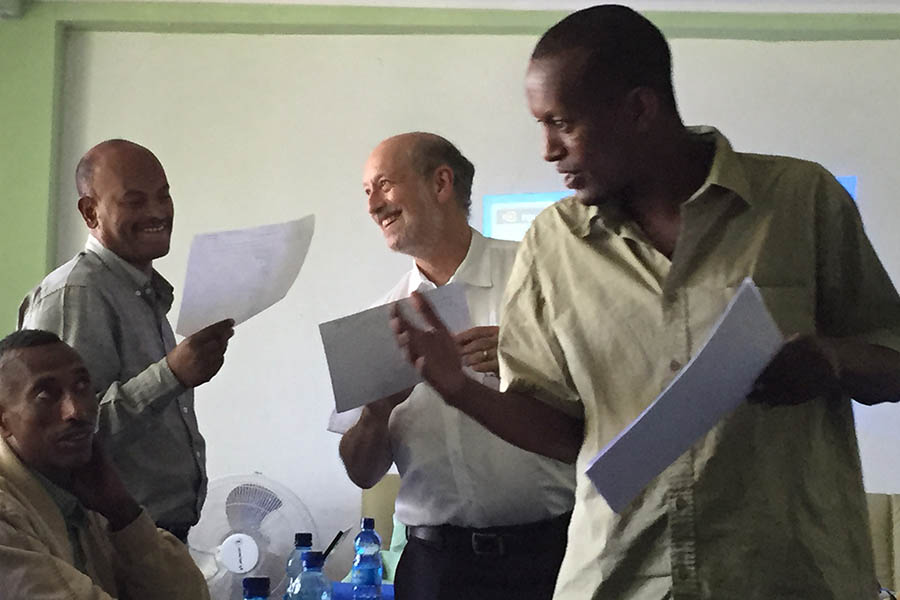

The support workers, who were trained by Lifson and colleagues in Ethiopia, came from the same areas as the clients they helped, and were taught how to provide HIV and health education, non-judgemental counseling and social support, and facilitate communication with the HIV clinic. “It’s a testament to the community support workers, who bring a tremendous personal dedication and commitment to the welfare of other people living with HIV,” says Lifson.

“Many clients expressed that their support worker understood their personal experiences and challenges,” says Lifson. “Social support such as that provided in this study may be strengthened when it comes from those who have effectively managed similar stressors and life circumstances.”

Based on the success of this pilot study, Lifson and colleagues are currently conducting a large community randomized trial funded by the NIH. The study is enrolling more than 1,700 patients from 32 hospitals and health clinics throughout southern Ethiopia.

“Trained support workers and peer counselors from a patient’s own community can provide a valuable addition and contribution toward optimizing the health of people living with HIV,” says Lifson. “We believe these lessons can be applied to many other settings throughout the world, not only for HIV, but also for the management of other chronic diseases.”